Not Just for Sci-Fi and RPGs

Cynical developers treat “business logic” as an oxymoron. Their business unit makes decisions, which are implemented by the development team into layers within an application. When the business unit decides, inevitably, to pivot on features or offerings, the development team has to scramble to heavily refactor their code in order account for new dependencies. When the business unit decides, inevitably, to pivot – again – on features or offerings, the development team has to scramble – again – to heavily reactor their code.

Thus “business logic” is all too frequently used as a euphemism for abstruse logic flows that are repeatedly rewritten until they make little sense, are highly untestable and brittle, include distracting swaths of dead and unused code, and generally complicate developers’ lives. However, all of this – especially the need for overly frequent refactoring – is more often than not purely the fault of the development team for failing to properly encapsulate business logic and separate it from other application layers. After all, they’re the ones actually writing – and thus controlling the quality of – the code.

This post is part of a series on building a RESTful Web-API Job microservice using .NET Core. The approach, design, and tools used herein are all based on my personal experience and should not be considered prescriptive. Some developers might like the approach, some might have different (and even better!) ideas. I’m open to suggestion, so feel free to hit the comments section on each post.

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) provides the best solution for decoupling business logic from its dependencies. The upshot is that the DIP specifies that business logic layer should declare its own dependencies as abstractions to be implemented by an adapter layer, which can be plugged in at runtime by the application layer. This is the foundation of the Hexagonal Architecture Pattern, also known as the “Ports and Adapters Pattern”.

Dogmatically implemented, Hexagonal Architecture stipulates that business logic libraries should take no dependencies. However, best-practice real-world implementations recommend that a limited whitelist of acceptable platform and company-specific abstractions be made available for business logic. The application can supply adapters tailored to the application’s more specific needs when it loads the business logic.

To illustrate the effectiveness of hexagonal architecture, the implementation for the Blueshift.Jobs microservice will start with a thin slice of the business logic layer. The most natural first set of types to add are the domain model: this is a Job microservice, so it’s time to add some Job types.

public class Job

{

public Guid JobId { get; set; }

public string JobOwnerId { get; set; }

public string JobDescription { get; set; }

public JobStatus JobStatus { get; set; }

public ISet<JobStatusChangeEvent> JobStatusChangeEvents { get; } = new HashSet<JobStatusChangeEvent>();

public IDictionary<string, string> JobParameters { get; } = new Dictionary<string, string>();

}

public enum JobStatus

{

None = 0,

Created = 1,

Pending = 2,

Completed = 3,

Failed = 4,

Cancelled = 5

}

public class JobStatusChangeEvent

{

public JobStatus PreviousStatus { get; set; }

public JobStatus NewStatus { get; set; }

public DateTimeOffset StatusChangedAt { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

}

These three types provide the basic functionality for tracking Jobs. Job has a unique JobId, a JobOwnerId, as well as a generic JobDescription for the proposed work to be accomplished. There’s a JobStatus to track the progress from creation to completion, and a set of timestamps for tracking when the Job moves through those various statuses. Finally, no job type would be complete without providing a simple key-value mechanism for parameters that allow for dynamic job execution.

Note that Job lacks an explicit “executable” declaration. For job types that might execute a CLI command or start an application, this might seem to be a key piece of missing functionality. However, this information belongs to specific job handlers, which are client-side implementations. The server-side portion should only store parameterized values that need to be provided to a handler at execution time.

Even then, the parameter values persisted to storage might not represent the actual value passed by the handler to the executable: handlers should be free to use values in the parameter set as means of modifying their own execution path at runtime. There will be more on this much, much later. For now, there’s still a server to implement.

Ostensibly, this microservice will, at some point, need to create, update, and delete Jobs. This functionality deals with persistence, which means it will undoubtedly come attached to an external dependency, most likely a particular database. Rather than implement it in the business logic library, it should just be abstracted as a Port using the Repository Pattern:

public interface IJobRepository

{

Task<IReadOnlyCollection<Job>> GetJobsAsync(JobSearchCriteria jobSearchCriteria);

Task<Job> CreateJobAsync(Job job);

Task DeleteJobAsync(Guid jobId);

Task<Job> GetJobAsync(Guid jobId);

Task<Job> UpdateJobAsync(Job job);

}

public class JobSearchCriteria

{

public string OwnerName { get; set; }

public ISet<JobStatus> JobStatuses { get; } = new HashSet<JobStatus>();

public int MaximumJobCount { get; set; }

public int JobsToSkip { get; set; }

}

The JobSearchCriteria class of note as it provides a mechanism to filter Jobs based on some given set of parameters. This can be useful for filtering Jobs by owner and/or status. It also provides a basic search result paging mechanism by way of MaximumJobCount and JobsToSkip.

So far, there’s no actual business logic. A basic domain model, a single repository port to be implemented externally. So what other functionality might a Jobs microservice provide beyond reading a writing Job instances from a database? With the JobSearchCriteria, there’s a clear route to an API endpoint that provides a list of Jobs available to another service. However, as designed, that request might not be idempotent.

There should be a way to codify a group of Jobs. Time to add a JobBatch and a repository for it:

public class JobBatch

{

public Guid JobBatchId { get; set; }

public string JobBatchDescription { get; set; }

public string JobBatchOwner { get; set; }

public DateTimeOffset CreatedAt { get; set; }

public ISet<Job> Jobs { get; } = new HashSet<Job>();

}

public interface IJobBatchRepository

{

Task<IReadOnlyCollection<JobBatch>> GetJobBatchesAsync(JobBatchSearchCriteria jobBatchSearchCriteria);

Task<JobBatch> CreateJobBatchAsync(JobBatch jobBatch);

Task DeleteJobBatchAsync(Guid jobBatchId);

Task<JobBatch> GetJobBatchAsync(Guid jobBatchId);

Task<JobBatch> UpdateJobBatchAsync(JobBatch jobBatch);

}

public class JobBatchSearchCriteria

{

public string OwnerName { get; set; }

public int MaximumJobBatchCount { get; set; }

public int JobBatchesToSkip { get; set; }

}

There’s still no business logic! This domain model object is still dependent on an external port. However, that port only deals with basic CRUDL operations around the lifetime of a JobBatch. Where could some actual business logic fit into this?

As written, these pieces would indicate that an external actor would need to fetch a set of Job instances, create a JobBatch around them, and then attempt to save that back to the Blueshift.Jobs microservice. That could run into concurrency issues and create performance bottlenecks across distributed services as the instances run into race conditions while trying to create job batches from the same pool of available Jobs.

Thus, the first piece of true business logic: requesting the Jobs microservice to generate a new batch for a given requestor.

public interface IJobBatchService

{

Task<JobBatch> CreateJobBatchAsync(CreateJobBatchRequest createJobBatchRequest);

}

public class CreateJobBatchRequest

{

public string JobBatchDescription { get; set; }

public string JobBatchRequestor { get; set; }

public JobSearchCriteria BatchingJobFilter { get; } = new JobSearchCriteria();

}

Finally, a service that can actually be implemented inside this business logic layer! Here’s a stab at an implementation:

public class JobBatchService : IJobBatchService

{

private readonly IJobRepository _jobRepository;

private readonly IJobBatchRepository _jobBatchRepository;

private readonly ILogger<JobBatchService> _jobBatchServiceLogger;

public JobBatchService(

IJobRepository jobRepository,

IJobBatchRepository jobBatchRepository,

ILogger<JobBatchService> jobBatchServiceLogger)

{

_jobRepository = jobRepository ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(jobRepository));

_jobBatchRepository = jobBatchRepository ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(jobBatchRepository));

_jobBatchServiceLogger = jobBatchServiceLogger ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(jobBatchServiceLogger));

}

public async Task<JobBatch> CreateJobBatchAsync(CreateJobBatchRequest createJobBatchRequest)

{

if (createJobBatchRequest == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(createJobBatchRequest));

}

_jobBatchServiceLogger.LogInformation(

BlueshiftJobsResources.CreatingJobBatch,

createJobBatchRequest.JobBatchRequestor,

createJobBatchRequest.JobBatchDescription,

createJobBatchRequest.BatchingJobFilter.MaximumJobCount);

try

{

IReadOnlyCollection<Job> jobs = await _jobRepository

.GetJobsAsync(createJobBatchRequest.BatchingJobFilter)

.ConfigureAwait(false);

var jobBatch = new JobBatch(jobs)

{

JobBatchOwner = createJobBatchRequest.JobBatchRequestor,

JobBatchDescription = createJobBatchRequest.JobBatchDescription

};

jobBatch = await _jobBatchRepository

.CreateJobBatchAsync(jobBatch)

.ConfigureAwait(false);

_jobBatchServiceLogger.LogInformation(

BlueshiftJobsResources.CreatedJobBatch,

jobBatch.JobBatchOwner,

jobBatch.JobBatchDescription,

jobBatch.Jobs.Count);

return jobBatch;

}

catch (Exception e)

{

_jobBatchServiceLogger.LogError(

BlueshiftJobsResources.ErrorCreatingJobBatch,

_jobBatchServiceLogger.IsEnabled(LogLevel.Debug)

? e.StackTrace

: e.Message);

throw;

}

}

}

Now it’s time for a simple test. This new service takes two repositories, but there’s no need to actually implement. The test will make use of Moq to generate testable instances of these interfaces with only the functionality required for the test to pass:

public class JobBatchServiceTests

{

private readonly TestJobBatchServiceFactory _testJobBatchServiceFactory;

public JobBatchServiceTests()

{

_testJobBatchServiceFactory = new TestJobBatchServiceFactory();

}

[Theory]

[InlineData(10)]

[InlineData(25)]

[InlineData(50)]

[InlineData(150)]

public async Task CreateJobBatchAsync_requests_the_expected_number_of_jobs_and_saves_the_batch(int requestedJobCount)

{

_testJobBatchServiceFactory.MockJobRepository

.Setup(jobRepository => jobRepository.GetJobsAsync(It.IsAny<JobSearchCriteria>()))

.ReturnsAsync((JobSearchCriteria jobSearchCriteria) =>

_testJobBatchServiceFactory.AvailableJobs

.Take(jobSearchCriteria.MaximumJobCount)

.ToList()

.AsReadOnly()

)

.Verifiable();

_testJobBatchServiceFactory.MockJobBatchRepository

.Setup(jobBatchRepository => jobBatchRepository.CreateJobBatchAsync(It.IsAny<JobBatch>()))

.ReturnsAsync((JobBatch batch) => batch)

.Verifiable();

JobBatchService jobBatchService = _testJobBatchServiceFactory.CreateJobBatchService();

var createJobBatchRequest = new CreateJobBatchRequest()

{

BatchingJobFilter =

{

MaximumJobCount = requestedJobCount

}

};

JobBatch jobBatch = await jobBatchService.CreateJobBatchAsync(createJobBatchRequest);

Assert.NotNull(jobBatch);

Assert.Equal(

_testJobBatchServiceFactory.AvailableJobs.Take(requestedJobCount),

jobBatch.Jobs);

_testJobBatchServiceFactory.MockJobRepository

.Verify(

jobRepository => jobRepository.GetJobsAsync(

It.Is<JobSearchCriteria>(jobSearchCriteria => jobSearchCriteria.MaximumJobCount == requestedJobCount)),

Times.Once);

_testJobBatchServiceFactory.MockJobBatchRepository

.Verify(

jobBatchRepository => jobBatchRepository.CreateJobBatchAsync(jobBatch),

Times.Once);

}

private class TestJobBatchServiceFactory

{

public IList<Job> AvailableJobs { get; } = Enumerable

.Range(0, 100)

.Select(index => new Job

{

JobId = Guid.NewGuid(),

JobDescription = $"Job Number {index}"

})

.ToList();

public Mock<IJobRepository> MockJobRepository { get; } = new Mock<IJobRepository>();

public Mock<IJobBatchRepository> MockJobBatchRepository { get; } = new Mock<IJobBatchRepository>();

public JobBatchService CreateJobBatchService()

=> new JobBatchService(

MockJobRepository.Object,

MockJobBatchRepository.Object,

NullLogger<JobBatchService>.Instance);

}

}

This test just asserts that the JobBatchService makes a request to the IJobRepository interface for the specified number of jobs, and then saves a JobBatch to the IJobBatchRepository before returning a non-null instance of the JobBatch.

This might not seem like a lot of functionality for a business logic layer, but it’s all that’s needed here. Business logic absolutely does not need to be complicated, or tightly coupled to external dependencies to be valid. And by separating out the layers appropriately, a lot of the complications that developers inject into their code can be outright avoided from the beginning of a project.

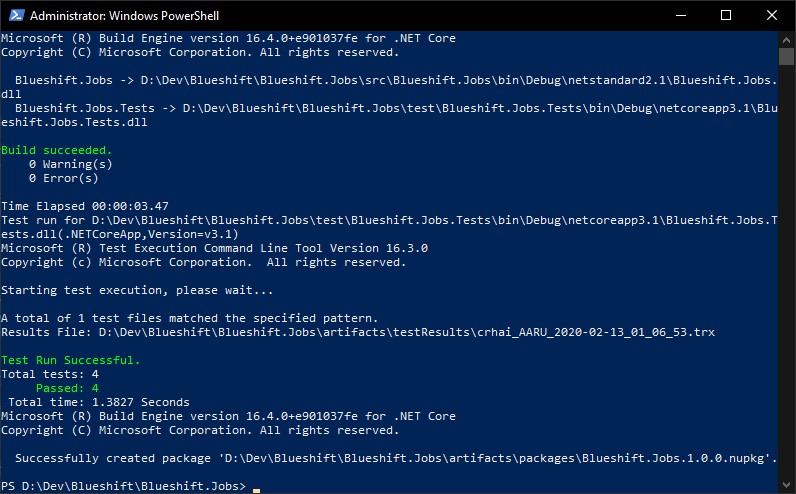

A quick call to Build.ps1 verifies that everything still works:

Now the code is in a great place to commit. As with the previous step, this one is very small and can be completed in well under an hour. This works well for Agile teams using Scrum and Kanban as it presents an easy deliverable for a small, quick story that can lead to greater team collaboration. There’s now working business logic, and a set of two thin repository ports to be implemented in an adapter layer.

And that’s the next step: a first-pass implementation of repository adapters!

You must be logged in to post a comment.