Oh, Were You Using That?

Once there is enough business logic in place, the development team can start implementing various integration and adapter layers. Nearly all web applications will, at some point, require a persistence layer. So a natural first place to look is any repository layer.

As stated at the very beginning of this microservice implementation, Hexagonal Architecture (or more generally, the Dependency Inversion Principle) makes it simple and straightforward to swap out technologies. To prove this, the first adapter implemented here will be an in-memory adapter for the business logic’s repository ports.

This post is part of a series on building a RESTful Web-API Job microservice using .NET Core. The approach, design, and tools used herein are all based on my personal experience and should not be considered prescriptive. Some developers might like the approach, some might have different (and even better!) ideas. I’m open to suggestion, so feel free to hit the comments section on each post.

In-memory repositories are great for development and testing. Ignoring the specifics of a database allows for the first integration step to focus on the performance of the business logic itself: what values and keys are necessary to guarantee uniqueness, and determining what, if any, other fields of the runtime objects might be involved in queries. When the application eventually moves to an actual database for persistence, having pre-refined searches that serve the business logic’s specific needs will help with defining the indexes necessary to make performant DB queries.

An in-memory repository needs a caching mechanism. The most basic kind is an IDictionary<,>, and it can be very tempting to “keep it simple” and use that. However, this might be tricky to get work correctly with dependency injection (a topic for later in the implementation of this microservice). It could also be a violation of the Interface Segregation Principle since dictionaries have a good bit more functionality than these repositories need. Also, if the data structure turns out not to be right for this implementation, it could take a bit more refactoring than absolutely necessary to fix later.

A simple custom object will do:

public interface ICache<TKey, TValue>

{

bool TryAddValue(TKey key, TValue value);

bool TryGetValue(TKey key, out TValue value);

bool TryRemoveValue(TKey key);

TValue SetValue(TKey key, TValue value);

IQueryable<TValue> Query();

bool HasKey(TKey key);

}

public class ConcurrentCache<TKey, TValue> : ICache<TKey, TValue>

{

private readonly ConcurrentDictionary<TKey, TValue> _dictionary

= new ConcurrentDictionary<TKey, TValue>();

public TValue SetValue(TKey key, TValue value)

=> _dictionary.AddOrUpdate(

key,

value,

(TKey existingKey, TValue existingValue) => value);

public bool TryAddValue(TKey key, TValue value)

=> _dictionary.TryAdd(key, value);

public bool TryGetValue(TKey key, out TValue value)

=> _dictionary.TryGetValue(key, out value);

public bool TryRemoveValue(TKey key)

=> _dictionary.TryRemove(key, out TValue value);

public IQueryable<TValue> Query()

=> _dictionary.Values.AsQueryable();

public bool HasKey(TKey key)

=> _dictionary.ContainsKey(key);

}

With this in hand, it’s time to implement IJobRepository. First, CreateJobAsync:

public Task<Job> CreateJobAsync(Job job)

{

if (job == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(job));

}

Guid jobId;

do

{

jobId = Guid.NewGuid();

}

while (!_jobCache.TryAddValue(jobId, job));

job.JobId = jobId;

return Task.FromResult(job);

}

This method attempts to find a key that’s not yet in the cache, and then assigns that value to the Job. There are key saturation and performance implications to this, but for Guid types it’s a bit unfeasible that a dev/test machine might run into those. For now, this implementation will suffice.

DeleteJobAsync, GetJobAsync, and UpdateJobAsync are all essentially passthru implementations:

public Task DeleteJobAsync(Guid jobId)

{

_jobCache.TryRemoveValue(jobId);

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

public Task<Job> GetJobAsync(Guid jobId)

=> _jobCache.TryGetValue(jobId, out Job job)

? Task.FromResult(job)

: Task.FromResult<Job>(null);

public Task<Job> UpdateJobAsync(Job job)

{

if (job == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(job));

}

job = _jobCache.SetValue(

job.JobId,

job);

return Task.FromResult(job);

}

The real meat of this repository is in the actual query. GetJobsAsync takes a JobSearchCriteria object that has several fields for controlling the query. While it can be tempting to just refactor GetJobsAsync to return an IQueryable<Job>, this violates a bit of the Dependency Inversion Principle as well as the Open/Closed Principle by tying the adapters to a specific underlying querying mechanism. The adapter layer would necessarily have to ensure that it complies to IQueryProvider semantics, and that’s no easy feat. So instead, the method takes search criteria and allows the adapter to figure out how to perform the query.

In the case of the in-memory Job repository:

public Task<IReadOnlyCollection<Job>> GetJobsAsync(JobSearchCriteria jobSearchCriteria)

{

if (jobSearchCriteria == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(jobSearchCriteria));

}

IQueryable<Job> jobQuery = _jobCache.Query();

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(jobSearchCriteria.JobOwnerId))

{

jobQuery = jobQuery.Where(job => job.JobOwnerId.Contains(jobSearchCriteria.JobOwnerId, StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase));

}

if (jobSearchCriteria.JobStatuses.Count > 0)

{

jobQuery = jobQuery.Where(job => jobSearchCriteria.JobStatuses.Contains(job.JobStatus));

}

if (jobSearchCriteria.ExecuteAfter.HasValue)

{

jobQuery = jobQuery.Where(job => jobSearchCriteria.ExecuteAfter >= job.ExecuteAfter);

}

jobQuery = jobQuery.OrderBy(job => job.ExecuteAfter ?? job.CreatedAt);

if (jobSearchCriteria.ItemsToSkip.HasValue)

{

jobQuery = jobQuery.Skip(jobSearchCriteria.ItemsToSkip.Value);

}

if (jobSearchCriteria.MaximumItems.HasValue)

{

jobQuery = jobQuery.Take(jobSearchCriteria.MaximumItems.Value);

}

IReadOnlyCollection<Job> jobes = jobQuery

.ToList()

.AsReadOnly();

return Task.FromResult(jobes);

}

Developers unfamiliar with Linq may see this as strange since there are multiple calls to the Where that can be reduced to a single lambda. However, Linq operates by deferred callbacks: that is, the lambda expressions aren’t evaluated until the very end of the method, when ToList is called to enumerate the queryable results. If all of the search criteria are specified, the Where calls would become chained and their predicates are functionally AND-ed together. This allows the search criteria properties to be processed individually, only adding the necessary predicates.

The adapter implementation for IJobBatchRepository is almost identical, assign from a few minor details in the GetJobBatchesAsync implementation. There’s no need to paste that code here.

Testing these implementation is very easy, if long-winded. Tests can use Moq to mock up instances of the ICache<,> interface and verify that the repository does what is expected:

[Theory]

[InlineData(1)]

[InlineData(10)]

[InlineData(100)]

public async Task CreateJobAsync_assigns_new_JobId_when_attempt_to_save_fails(int iterations)

{

var job = new Job();

int count = 0;

_testMemoryCacheJobRepositoryFactory.MockJobCache

.Setup(jobCache => jobCache.TryAddValue(It.IsAny<Guid>(), job))

.Returns((Guid guid, Job batch) => count++ < iterations ? false : true)

.Verifiable();

var memoryCacheJobRepository = _testMemoryCacheJobRepositoryFactory

.CreateMemoryCacheJobRepository();

Assert.Equal(Guid.Empty, job.JobId);

Assert.Same(job, await memoryCacheJobRepository.CreateJobAsync(job));

Assert.NotEqual(Guid.Empty, job.JobId);

_testMemoryCacheJobRepositoryFactory.MockJobCache.Verify(

jobCache => jobCache.TryAddValue(

It.Is<Guid>(guid => guid != job.JobId),

job),

Times.Exactly(iterations));

_testMemoryCacheJobRepositoryFactory.MockJobCache.Verify(

jobCache => jobCache.TryAddValue(job.JobId, job),

Times.Once);

}

This test theory mocks up the interaction between the repository and the cache, verifying that the repository re-assigns the JobId on insert if there are any collisions with (up to at least 100) existing ids.

There are many more tests like this. And as with the two highly similar repositories, their tests have significant overlap. So there’s not much point in going over the specifics of the MemoryCacheJobBatchRepositoryTests implementations.

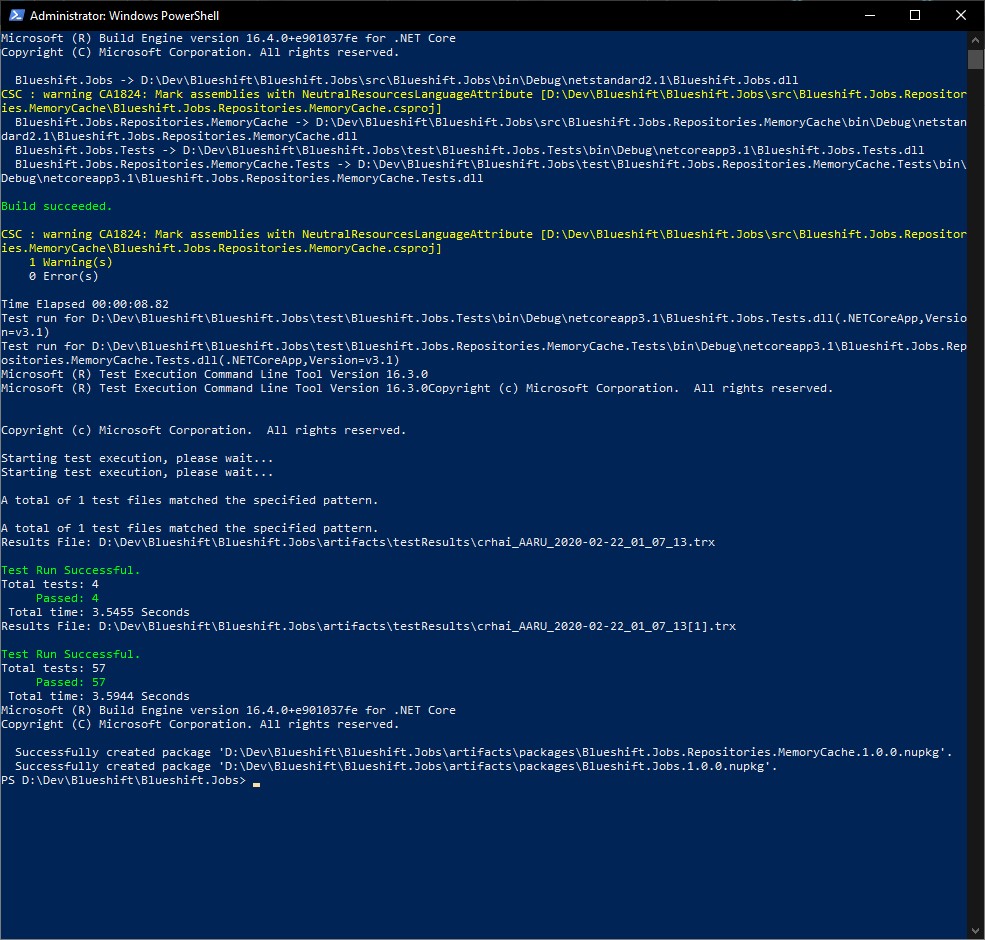

It’s time to verify that the build still works:

With the in-memory repositories and relevant tests written, now is a great opportunity to check in code. Note the extra commit to make the SearchCriteria objects consistent. These changes came up during the implementation of the MemoryCache repository. Keeping them in a separate commit allows them to go through code review and approval processes that prevent them from being tied directly to the specific adapter. If the changes to the business logic aren’t approved, then a different approach can be taken to inject consistency.

Having an implementation of a set of repositories will allow upstream implementations and integrations – such as the actual Web API controllers – to move forward.

That sounds like a great next step: Web API controller implementation!

You must be logged in to post a comment.